In military science, strategic deception is defined as “a series of meticulously planned and synchronized actions designed to camouflage details of ongoing preparations for an anticipated attack, whose disclosure to the enemy could influence the broader trajectory of the war.” These actions span a broad spectrum, encompassing not just tactical or operational dimensions but also political, economic, and media efforts linked to the preparations for the attack. The primary objective is to prevent enemy intelligence services from accurately assessing the strategic and tactical situation, instead diverting their analyses and resources toward misleading directions, ultimately leading to decisions that favor friendly forces.

In this vein, the element of surprise can be regarded as one of the most crucial factors that the Egyptian political and military leadership prioritised during the planning and preparation stages of the offensive operations in the October War. The unfolding of the battlefield events, along with the ‘confusion’ and ‘tension’ that gripped the Israeli military leadership in the early days of the conflict, demonstrated that this element was achieved with remarkable precision. Moreover, the “strategic deception plan” employed by the Egyptian leadership to maintain the secrecy of the rigorous preparations for the liberation battle became a pivotal turning point that determined the war’s outcome and marked a shining chapter in military history at every level.

I. Phases of Designing the Strategic Deception Plan

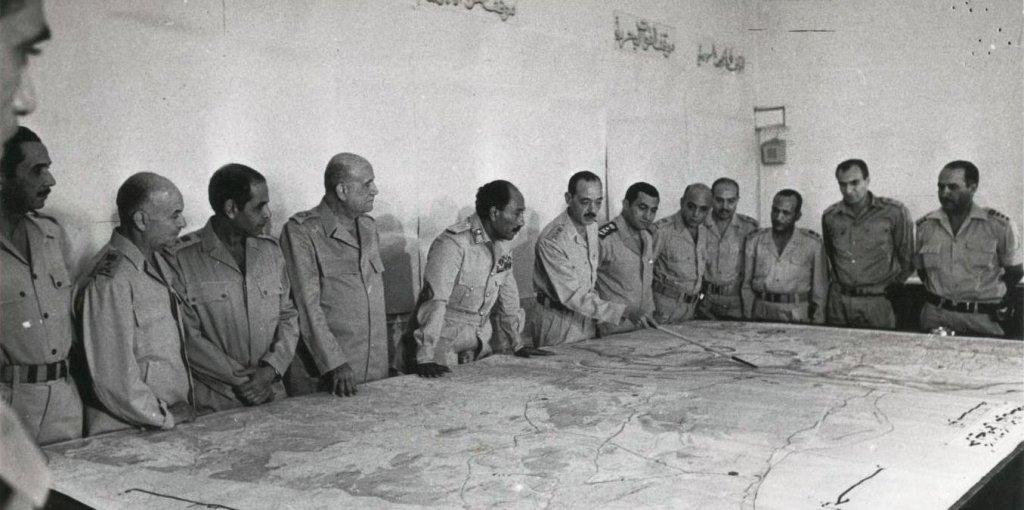

The development of the strategic deception plan, which supported the overall offensive strategy, began in mid-May 1971 when the Egyptian political leadership appointed Field Marshal Ahmed Ismail to lead the General Intelligence Service. He was entrusted with the task of drafting the strategic deception plan, addressing both its civilian and military dimensions. Ismail immediately started working with the Military Intelligence Service and the Military Operations Authority of the Armed Forces, where the Planning Branch took the lead in coordinating with General Intelligence and Military Intelligence Services to shape the final elements of the plan. The initial version of the strategic deception plan was presented for discussion in early July 1972, during a meeting chaired by the late President Anwar Sadat at the General Intelligence Service’s headquarters, in the presence of senior military leaders, the head of military intelligence, and the heads of key divisions within general intelligence.

During this meeting, Sadat underscored the crucial role of the strategic deception plan as a fundamental tool to counterbalance the disparity in military, scientific, and technological capabilities between Egypt and Israel. He emphasized the absolute necessity of maintaining complete secrecy regarding any potential Egyptian offensive operation, especially considering Israel’s readiness with preemptive strike plans targeting Egyptian military sectors should it detect any signs of Egypt preparing for an offensive towards the east of the Suez Canal.

Egypt’s strategic deception plan primarily relied on uniting the efforts of all key state bodies, led by the ministries of media, foreign affairs, and war, approximately six months before the commencement of actual military operations. These efforts were aligned with military deception tactics to implement a series of actions, statements, movements, and initiatives aimed at achieving two core objectives. The first was to obscure Egypt’s military readiness to conduct offensive operations, creating the false impression that the country had no intention of entering a conflict in the foreseeable future. The second was to conceal the precise timing of the joint Egyptian-Syrian attack for as long as possible, preventing any disruption of Egyptian and Syrian preparations and safeguarding the element of surprise, a critical factor in determining the final outcome of such offensive operations.

The actual implementation of the plan effectively commenced on October 26, 1972, with the appointment of Ismail as Minister of War, marking the launch of the plan’s implementation phases. These phases encompassed political, media, and internal aspects, in addition to military elements, with one of the most critical being the determination of the timing for initiating combat operations. Contrary to common belief, this issue was characterized by a high degree of risk and complexity, and success in managing it became a key factor that allowed Egyptian and Syrian forces to achieve an extraordinary level of surprise, which was clearly reflected in the battlefield dynamics and the overall outcomes of the combat operations.

II. The Political Aspect of the Strategic Deception Plan

A key element of strategic deception plan was the direct involvement of Egypt’s highest political authority, embodied by President Sadat, in its execution, alongside all governmental executive bodies. Sadat was committed to projecting an image to the world that carried a sense of ‘contradiction,’ implying that Egypt’s strategic choices excluded any military action towards the east of the Suez Canal and instead were focused purely on reinforcing defensive positions.

This contradictory narrative, deliberately crafted by the Egyptian political leadership and aimed at influencing Israeli decision-makers, took shape through a series of sweeping statements. The most notable of these was made by Sadat on June 22, 1971, during his address to naval officers at the Abu Qir naval base, in which he said: “I speak to you and our people with complete honesty and clarity: 1971 is a critical year, and we cannot afford to wait indefinitely. Let us, therefore, remain ever prepared.” However, the following year, on January 13, 1972, Sadat implied a completely different message in a speech before Parliament, stating: “I stated that 1971 would be the year of decision, and my orders to the Commander-in-Chief, General Sadek, were fully prepared and executed to the last phase. I halted the process, as I explained before, due to the fog—much like the fog on Sunday, July 9, 1967—though this time it unfolded in Southeast Asia, with the Soviet Union, my ally in this battle, being part of it.” This deliberate contradiction, coupled with the rise of student protests in Egypt starting on January 15, 1972, contributed to the effectiveness of the Egyptian strategic deception plan, reinforcing the perception of “Egypt’s unwillingness to engage in war,” which Cairo sought to project to Tel Aviv.

Sadat reinforced this narrative by issuing a presidential decree on July 17, 1972—roughly a year after signing the friendship treaty with the Soviet Union—to terminate the presence of approximately 20,000 Soviet military experts. This move sent an initial signal to Tel Aviv that tensions between Cairo and Moscow over military supplies had reached a breaking point and that the Soviet Union’s engagement in détente discussions with the United States had substantially narrowed Egypt’s scope for military maneuvering, signaling a complete retreat from any military action on the front lines.

The Egyptian strategy of camouflage and deception also encompassed the activities and movements of diplomats, ministers, and just before the onset of military operations. Alongside the Egyptian Foreign Minister’s visit to the United States, the Minister of Finance and Economy, Abdel-Aziz Hegazy, journeyed to Britain, while the Minister of Transport and Communications, Al-Husseini Abdel Latif, travelled to Spain. Additionally, reports circulated that the Minister of Defense’s wife had been admitted to a hospital in London for urgent surgery. Concurrently, Egyptian embassies abroad began to highlight Egypt’s unpreparedness for any military conflict at that time.

III. Preparing the Domestic Front

On the home front, the strategic deception plan required action on two key tracks. First, it was essential to prepare the domestic front for the demands of initiating offensive operations, and second, to reinforce the broader elements of the strategic deception plan. A critical step involved evacuating several hospitals and preparing them to receive the wounded at the onset of the battle—a fundamental principle of war preparedness. However, since such a large-scale measure would inevitably attract the attention of Israeli intelligence, the Egyptian military planners needed to devise a strategy that would enable the hospital evacuations without raising any suspicion.

To accomplish this, a meticulously crafted plan was developed, which involved the discharge of one officer from the medical corps, allowing him to return to his previous position at Demerdash Hospital, affiliated with Ain Shams University. This hospital was chosen due to its significant capacity, placing it at the forefront of the list. In line with the plan, the doctor arrived at the hospital to find that the main wards for patients were infested with the tetanus bacteria. Alarmed by this perilous threat to patient lives, he promptly dispatched several messages to the Ministry of Health. Consequently, the Ministry mandated a full evacuation of the hospital, followed by an extensive disinfection. The doctor was then assigned to inspect the remaining hospitals to gauge the extent of contamination. Newspapers reported extensively on the situation, featuring investigative articles about the contaminated facilities and photographs of disinfection teams spraying pesticides in the wards. This strategy successfully led to the evacuation of the required number of hospitals by the beginning of October, ensuring they were fully prepared to receive the wounded and injured as a crucial precaution for the impending military operations.

Securing food supplies, too, posed a significant challenge in the context of war preparations, as the availability of ample reserves of strategic commodities like wheat, sugar, and rice was just as crucial as ensuring sufficient ammunition and weapons for the armed forces. It was therefore essential to import and store enough of these commodities, especially wheat, due to the logistical difficulties that would arise if imports were disrupted by the onset of military action. However, these procurement efforts had to be carried out discreetly to avoid alerting Israeli intelligence to the looming military operations. To achieve this, Egypt’s General Intelligence Service intentionally leaked information suggesting that local wheat reserves had suffered severe damage due to various factors, including flooding caused by winter rains, fires in multiple silos, and the contamination of stored wheat by a fungus. This narrative turned into a media scandal, allowing Egypt to discreetly import the necessary quantities of wheat without raising suspicions.

Alongside these efforts, another series of measures was implemented to bolster military operations and execute the strategic deception plan. Among these was the acquisition of water pumps, which the engineering corps would utilize to breach the earthen berm. The process of importing these pumps was carefully orchestrated to avoid triggering Israeli suspicions. To this end, a group of agricultural and irrigation engineers, along with civil defence officers, travelled separately to Germany and Britain. Their mission was to purchase heavy-duty water pumps and fire-fighting water cannons, under the guise of securing equipment for an irrigation project Egypt had announced in 1972, which aimed to cultivate 900,000 acres of vegetables over a five-year period.

IV. The Field Aspect

The military planner, while crafting the military side of the strategic deception plan, hinged on exploiting a fundamental weakness in Israel’s security theory: its complete dependence on a 48-hour advance warning to activate its reserves. This crucial flaw became the cornerstone of the military aspect of Egypt’s strategic deception plan, which involved concealing the buildup of forces and perpetuating the impression of Egyptian forces being complacent and unprepared for any offensive actions, apart from routine exercises and scheduled maneuvers. Cairo skillfully leveraged the fundamental assessments Israeli military intelligence relied on when analyzing Egypt’s intentions, using these assessments to its strategic benefit.

From the outset of 1972, Israeli military circles became convinced that Egypt would only engage in combat if two fundamental conditions were fulfilled: the acquisition of long-range fighter bombers capable of conducting strikes deep into Israeli territory and the development of ballistic missile capabilities, specifically the Soviet Scud missiles. This conviction emerged from a variety of factors, with the most significant being the persistent focus on these two military assets during the visits of Egyptian political figures. For instance, the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser brought up this topic with Soviet officials during his January 1970 visit to Moscow, while Sadat brought up the same matter during his August 1972 meeting with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev.

In light of this assessment, Israeli military intelligence concluded that the Egyptian military preparations were not indicative of offensive plans but were instead part of the regular training exercises conducted by the Egyptian forces. This notion was further reinforced by a general evaluation from Israeli military intelligence in April 1973, which asserted that the likelihood of the Egyptians launching offensive operations was minimal and that the Syrian forces, although showing signs of readiness for combat, still lacked essential military components. Israel’s persistent confidence in this assessment was likely bolstered by various tactical measures undertaken by Egypt to conceal its preparations for the impending crossing operation.

The first of these measures involved the construction of an earthen berm on the western bank of the canal toward the end of 1972, a venture that cost around EGP 30 million. Although the main aim behind this barrier was to bolster defense against any Israeli incursions, it effectively served to obscure the substantial deployment of Egyptian artillery and tanks. After its completion, several similar sand barriers were erected along the rear lines, enhancing this concealment. As a result, these barriers fulfilled their purpose by leading the Israeli military to believe that the Egyptian forces were pursuing a defensive strategy to protect these barriers.

The transportation of heavy military equipment and tanks to the front lines was a crucial element of the military deception plan. When it was time to dispatch tank convoys, the main repair facilities were relocated closer to the front, and tanks were then sent in lines under the guise of being damaged. Israel interpreted this movement as an indication of a severe decline in the operational state of Egyptian armored vehicles, stemming from a lack of spare parts following the withdrawal of Russian experts. This maneuver further obscured the true reasons behind the significant concentration of tanks near the Suez Canal. Additionally, Egyptian military planners devised an ingenious ruse reminiscent of the ‘Trojan Horse,’ constructing large mock models of tanks designed to conceal actual military equipment or real tanks inside them, enabling a deceptive presence of numerous tanks hidden within these structures.

The logistics of transporting engineering equipment for crossing the Suez Canal, particularly rubber boats, presented a significant challenge. A critical question loomed over how to import such a large number of rubber boats without drawing Israeli scrutiny. This conundrum was cleverly resolved by shipping the boats on civilian vessels to the port of Alexandria, where they were left unattended on one of the docks for two days, creating an impression of negligence and indifference. Afterward, army trucks transported half of the boats to a desert location near Helwan, stacking them in plain sight on terraces to make them appear twice their actual size, while worn-out nets were draped over them that revealed more than they concealed. Meanwhile, civilian trucks, marked with the logo of a private contracting company, discreetly delivered the remaining boats directly to the front, hiding them within the aforementioned structural models. This meticulously crafted plan also included transporting the crossing bridges in disassembled segments on special vehicles exclusively at night. Strict orders were issued to refrain from inflating the crossing boats until the airstrike commenced, as tests had shown that the sounds of inflating could be detected up to 800 meters away.

Concerning the infantry forces, the Egyptian military planner turned to developing a comprehensive mobilization plan and reinstating the call-up of reserve forces after the 1967 decision to halt the transfer of soldiers to reserve status. This plan also included the demobilization of roughly 30,000 soldiers in July 1972 and the regular recall of reserve officers and soldiers. In total, 22 call-ups took place before the crossing, with the 23rd initiating operations. This routine reserve mobilization created the illusion for Israel that the Egyptian army had no immediate intent to engage in battle. Additionally, Egypt repeatedly leaked misleading information, suggesting large-scale military actions in December 1971, April 1972, May, and August 1973, prompting Israel to declare general mobilization on several occasions while Egyptian forces remained at ease. This imposed considerable financial and logistical pressure on Tel Aviv, forcing it to reconsider any future mobilization efforts, which worked in Egypt and Syria’s favor by October 1973.

The training operations for the crossing forces necessitated a separate plan designed to gradually deceive Israeli intelligence through frequent, periodic training exercises. Throughout the summer of 1972, Egyptian forces trained openly to cross the canal in full view and within earshot of the enemy, as they prepared landing beaches. In 1973, the Egyptian army even conducted a scaled-down simulation of the crossing, minimizing the operational details. Egyptian newspapers covered this exercise, and enemy soldiers stationed in their trenches on the eastern bank of the waterway observed the entire operation.

These periodic training operations included the announcement of a military exercise in 1973 named Liberation 23, conducted from October 1-7. This maneuver was part of a strategic mobilization project, repeated multiple times annually, during which full-scale offensive procedures were practiced, including troop movements, force deployment, raising the army’s readiness to its highest level, and declaring a state of alert at airports and air bases. Indeed, this exercise served as a cover for discreet Egyptian military movements along the front in preparation for the crossing operation. It took 3-4 months to assemble the crossing forces, with units gradually pushed forward in small detachments, while the required supplies were gathered at the front three weeks prior to the attack, all under the guise of conducting engineering work related to the aforementioned project.

The deployment of the armed forces along the Egyptian front over the years served as further proof of the effectiveness of the strategic deception plan. This gradual approach allowed for the mobilization of the necessary forces without attracting attention to the buildup, which included five infantry divisions in the first echelon, followed by two armored divisions positioned 25 kilometers behind in the second echelon. The war plan was designed to ensure that mobilization operations would not require significant changes on the ground, which could have exposed Egypt’s intentions to Israeli aerial reconnaissance. It hinged on five infantry divisions storming the Suez Canal, with each division targeting a specific sector that it had already been responsible for defending while stationed on the western bank. This approach minimized unnecessary movements, which, if made, could have alerted the enemy to the impending operation.

The Egyptian Air Force remained in a constant state of training and alert in the lead-up to the crossing, leveraging the ‘Liberation 23’ war exercise as a justification for heightened readiness and declaring a state of alert at all airports and air bases. As a result, Tel Aviv closely monitored the continuous Egyptian air sorties around various airports, deploying its own aircraft in anticipation of potential Egyptian offensives. This routine throughout September played a crucial role in leading Israeli Air Force commanders to believe that the Egyptian air movements on the afternoon of October 5 were part of regular air training exercises. This perception was further strengthened by the Egyptian Air Force’s announcement that the commander of the force would be traveling on an urgent mission to Libya on October 5, which was then delayed to the following afternoon, aligning with the real timing of the first air strike.

At the naval level, to disguise their plan to block the Bab el-Mandab Strait at the onset of military operations, a news report was published in September 1973, stating that three Egyptian naval vessels were en route to a Pakistani port for routine maintenance and overhaul. In fact, these vessels moved to Aden, where they remained for a week. They were then ordered to proceed to a Somali port for an official visit, which lasted another week. Afterward, the vessels returned to Aden, where they received a coded message on the evening of October 5, 1973, directing them to discreetly position themselves at key locations in the Bab al-Mandab Strait. These positions allowed them to monitor, by radar, all ships passing through the Red Sea, inspect them, and prevent Israeli vessels from crossing the strait.

V. The Genius of War’s Timing

The determination of the exact ‘zero hour’ was a remarkable feat of scientific precision, making it an exceptional moment in the history of warfare. This decision, carefully selecting the most optimal time for the offensive, played a critical role in ensuring the element of surprise. However, this was far from an easy task, as it required meticulous consideration of the ideal month, day, and hour to launch the operation.

To ensure the effectiveness of these decisions, the Egyptian military leadership conducted thorough studies to assess the potential dates for launching the crossing. These dates had to meet two critical criteria: first, the expected weather, geological, and hydrographic conditions had to align with the demands of the offensive operations on both fronts simultaneously. Second, the selected date had to align with the strategic deception plan, ensuring the success of the crossing operation while maintaining the element of surprise until the very last moment.

The proposed dates for the commencement of military operations were outlined in a working paper submitted to President Sadat by Field Marshal Ismail in early April 1973. The options included launching the offensive in May, August, or between September and October. These proposals were further discussed in a critical meeting held in Cairo from August 21-23, which brought together Egyptian and Syrian military leaders in an atmosphere of strict secrecy and heightened security. During this meeting, the decision was made to schedule the attack between October 5 and 11, a date that was later solidified after Field Marshal Ismail’s visit to Syria on October 2, ensuring both Egypt and Syria were in agreement on the final timing for the commencement of offensive operations.

Determining the timings for the Egyptian-Syrian attack involved multiple stages. The first step was selecting the ideal month, considering the need for favorable weather conditions for the Egyptian and Syrian forces while simultaneously being disadvantageous to the enemy. Moderate weather and favorable climate were crucial for the success of the Egyptian forces in crossing the Suez Canal, so it was imperative to avoid late autumn and the onset of winter, when hydrographic conditions in the canal would be unfavorable. Similarly, on the Syrian front, the snowfall season begins in late November and early December, which also influenced the choice of date. Additionally, the selected month had to account for all factors that could facilitate a complete surprise, particularly with respect to Israel’s internal conditions. It was determined that the most suitable month would be one that coincides with major holidays and events when official media in Israel would be shut down, thereby affecting the efficiency of Israel’s reserve call-up process.

October presented the perfect alignment of conditions for launching the attack. Israel was preparing for the Knesset elections on October 28, and the month was marked by significant Israeli religious holidays such as Yom Kippur, Sukkot, and Torah. The overlap of these events with the holy month of Ramadan added another layer of advantage, providing a boost to Egyptian morale and enhancing the strategic surprise of launching the attack during the fasting period, which Israel did not anticipate. Furthermore, October offered long nights, with darkness lasting about 12 hours, which was advantageous for conducting operations under cover. Additionally, the month provided ideal weather conditions, not only for the naval operations but also for operations on both fronts.

Egypt carefully selected the appropriate day for the attack, aiming for a time when Israel would be celebrating an official holiday, a religious celebration, or a weekend, so that the country’s activities would be slowed or halted. Furthermore, it was essential that the tidal difference be minimal to facilitate the construction of crossings and bridges over the Suez Canal. Additionally, bright moonlight, especially in the first half of the night, was crucial for constructing ferries and bridges during the night, with the crossing itself to take place in the darkness of the second half. The moonlight needed to last for at least 5-6 hours before setting. All these conditions were perfectly aligned on October 6, 1973. It was Yom Kippur, a Saturday, and a weekend in Israel, with the media completely shut down, hampering the effectiveness of Israel’s reserve call-up process. Moreover, it was the tenth day of Ramadan, with favorable moon conditions, and the water levels in the canal were ideal, set to increase with the full moon.

In determining the precise moment to begin military operations, the Military Operations Authority of the Armed Forces conducted a study that aimed to ensure that the Syrian and Egyptian air forces could carry out a focused air strike during daylight, with the option to repeat it before the day’s end if the situation called for it. Simultaneously, the timing was chosen to prevent the Israeli air force from launching an intensive response before dusk. The study also considered favorable weather conditions that would facilitate the monitoring and correction of artillery fire during preparatory bombardments and in the initial hours after the crossing, while ensuring that sunlight would impair the enemy’s ability to observe and aim as Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal.

In line with these conditions, the time of the attack was selected to occur just before the last light of day, providing a brief but crucial window for executing the essential tasks required for the day’s combat operations, namely coordinating the joint airstrike; transporting the bridges from their rear assembly zones to the western bank of the canal; beginning their deployment into the water; carrying out the artillery prelude, with four concentrated bombardments lasting 53 minutes and utilizing approximately 2,000 cannons; and opening the passages in the earthen embankment. Prior to all these, commando forces were inserted deep into Israeli positions in Sinai to hinder the advancement of Israeli armored reserves and create confusion in Israel’s command and control systems, along with disrupting their transportation and communications networks.

The date for the commencement of military operations was kept completely confidential, even from the officers and soldiers involved. Commanders of the Second and Third Armies were informed on October 1, division commanders on October 3, brigade commanders on October 4, battalion and company commanders on October 5, and platoon commanders and soldiers were notified only six hours before the attack. The secrecy extended even to the Soviet military advisors in Cairo, who remained unaware of the impending offensive until October 4, prompting them to begin evacuating a large number of their advisors and families from Egypt.

In conclusion, Egypt’s strategic deception plan succeeded in creating significant confusion within Israeli military intelligence. Despite a number of important tactical and field indicators—such as the withdrawal of Moscow’s advisors from Egypt and Syria just two days before the operations, the deployment of Egyptian bridge battalions near the canal, the opening of gaps in minefields, and the heightened state of readiness in the Egyptian navy—Israeli intelligence dismissed these as unrelated events. Tel Aviv perceived them as either related to the rising tensions on the Syrian front or as routine training activities, posing no immediate threat. As a result, Israel found itself —for the first time in its history— on the receiving end of the blow rather than delivering it.