Over the past few years, several logistics projects have been proposed, centred on the strategic exploitation of geographical locations by one or more allied countries, with the aim of developing logistics corridors that facilitate regional and global trade routes, particularly those linking East Asia, Western Europe, and the United States. These projects range from oceanic and open-sea waterways and artificial canals for maritime transport to land corridors employing railways, roads, and pipelines for transporting goods and petroleum products. Moreover, there are multi-modal corridors that merge land and sea routes to facilitate the trading of goods.

These new projects are viewed as potential future rivals to the Suez Canal, as they could divert trade from this critical Egyptian waterway, which is currently the world’s most significant industrial shipping lane, which would adversely affect the Suez Canal’s revenue and, by extension, the broader Egyptian economy. Indeed, serious doubts linger over whether some of these competing projects could be realized or find success if ever attempted, rendering the narrative about the Suez Canal’s potential inadequacy over the medium and long term inaccurate.

This necessitates an analysis of the progress made in implementing and operating these projects to accurately assess the likelihood of the Suez Canal losing some of its traffic in the future. We will investigate this in an article series titled “The Suez Canal Amidst Global Competition.” This first article will examine waterways that are considered potential future competitors to the Suez Canal and are expected to accommodate large ships without the need for loading or unloading, unlike multimodal routes. Currently, six such waterways have been proposed—five spanning various continents and one located in the Middle East. They are as follows:

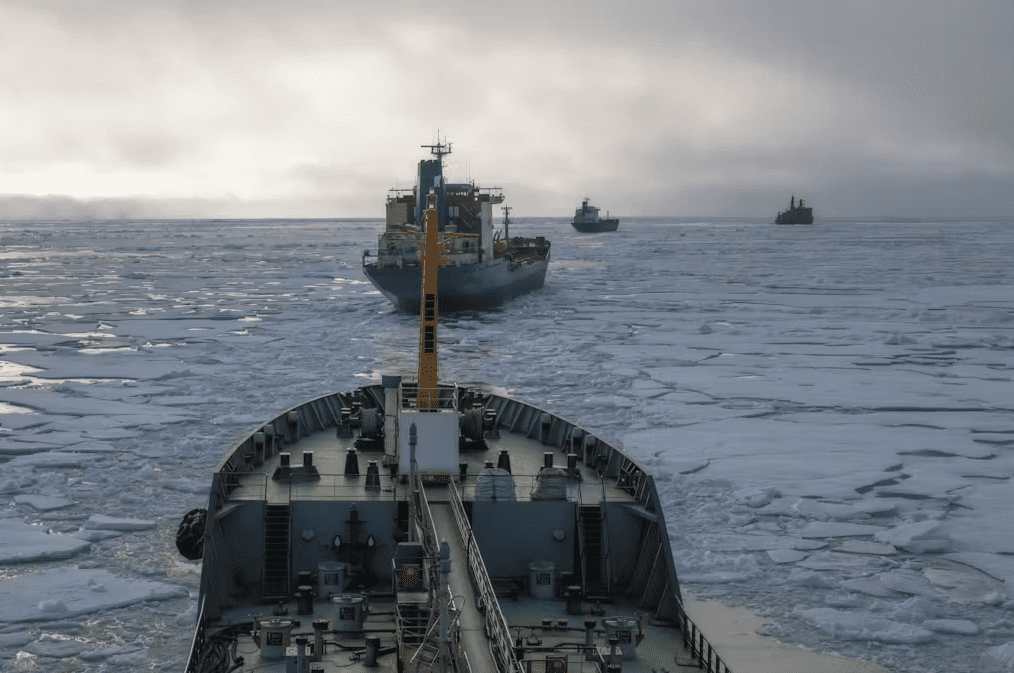

1. Russia’s Northeast Passage

This route stands out due to its relatively short distance between East Asia and Northwest Europe, covering less than 8,000 nautical miles between the Sea of Japan and the Norwegian Sea, compared to over 12,000 nautical miles via the Suez Canal as depicted in figure 1. The route also benefits from a lack of bottlenecks or security issues along its path. However, its drawback lies in its seasonal availability, being accessible only for a few summer months when snow density is lower. Additionally, it requires specialized equipment, such as icebreakers, to navigate its iceberg-laden waters.

Figure 1: The Northeast Passage’s route in comparison to the Suez Canal’s route

Source: An ABC News report titled “Moscow is betting big on its Arctic shipping route as the costs of invading Ukraine continue to mount”

Climate change impacting the North Pole has unveiled new opportunities for this corridor. Scientists anticipate that within three decades, the areas along northern Russia’s coast will be free of snow during the summer, enabling Russia to tap into oil and gas reserves beneath these regions and facilitating open navigation between East Asia and Western Europe for three months each year. This potential prompted the Russian government to unveil a RUB 1.8 trillion ($30 billion) plan in late 2022, aimed at developing infrastructure projects for transit trade in this emerging corridor and establishing a fleet of ice-strengthened commercial vessels, enabling the annual transport of 160 million tonnes of goods by 2035 and supporting China’s Polar Silk Road project.

2. Canada’s Northwest Passage

This route comprises a network of passages weaving between the northern coasts and islands of Canada, as shown in figure 2. This passage could shorten the distance between East Asia and Western Europe to under 10,000 nautical miles, compared to over 12,000 nautical miles via the Panama Canal and nearly 14,000 nautical miles via the Suez Canal.

Figure 2: The route of Canada’s Northwest Passage

Source: Northwest Passage Map, Encyclopedia Britannica

Despite its logistical edge, the Northwest Passage has not secured a prominent place in international maritime navigation due to several barriers that impede its advancement and optimize its advantages. These include the treacherous polar landscape, with its perilous icebergs that jeopardize ship safety, inadequate infrastructure for maritime trade, and a contentious political dispute between the United States and Canada over whether the corridor should be under Canadian exclusive control or designated as an international passage, a matter of considerable importance to US security and economic interests.

3. Panama Canal

In the 19th century, Colombian authorities envisioned a project akin to the Suez Canal, aiming to create a waterway connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The narrow Isthmus of Panama (shown in figure 3) offered a compelling opportunity for this venture. Beginning in 1881, the French, under the leadership of Suez Canal engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps, endeavored to assist Colombia with this ambitious project. However, the endeavor was plagued by severe challenges, including grueling excavation conditions caused by heavy rains, dense forests, and the prevalence of venomous reptiles and disease-carrying insects. These issues resulted in high worker mortality rates and led to the cessation of French efforts in 1889, which had already consumed nearly $300 million from international investors.

Figure 3: The Isthmus of Panama

Source: Map of the Isthmus of Panama dating back to 1904, Pennsylvania State University

The United States successfully completed the project the French had begun, overcoming previous obstacles, and the Panama Canal was inaugurated for international navigation in 1914. It quickly became the second most crucial man-made global shipping waterway after the Suez Canal and the primary conduit linking the Americas’ East and West. The canal’s lock-based engineering design enabled the passage of approximately 700,000 commercial ships over a century. However, in recent decades, the Panama Canal has struggled to accommodate vessels with deadweights exceeding 90,000 tonnes, failing to keep pace with evolving maritime demands and the growing size of ships seeking to transit.

In response to this challenge, the Panamanian government initiated the Third Set of Locks project in 2016, enabling the passage of ships with a deadweight of up to 160,000 tonnes through the Panama Canal. This upgrade boosted the canal’s share of global trade to 6% annually, up from a mere 4% in 2010. However, despite this progress, the Panama Canal still lags behind the Suez Canal, which accommodates vessels with a deadweight of up to 240,000 tonnes.

In the latter half of 2023, the Panama Canal was hit by an unprecedented crisis: the drying up of the freshwater lakes that supply its locks. This unexpected challenge forced a reduction in the number of daily transits to just 22 ships, slashing the canal’s operational capacity by 40%. The situation has also caused a significant pileup of vessels, with waiting times stretching over twenty days, threatening to disrupt $270 billion in global trade and potentially costing the canal authorities more than $600 million in annual revenue losses.

While the Panama Canal is expected to recover from its crisis by 2025, the looming threat of climate change may lead to recurrent droughts, diminishing the canal’s attractiveness to global shipping routes concerned about operational disruptions. This emerging challenge has prompted Panamanian officials to seek out effective engineering strategies to preserve the water levels essential for the locks’ functioning. In this context, it can be noted that the Panama Canal’s primary focus in the near future will be on sustaining the pre-drought traffic volume of 14,000 ships annually, while any plans for development and expansion are likely to be deferred for the short and medium term.

4. Nicaragua Canal

For centuries, Nicaragua’s ruling authorities aspired to establish a waterway that would seamlessly connect the eastern and western coasts of North and South America, easing the transport of goods and sparing commercial vessels the perilous routes around northern Canada or the Cape Horn in southern Latin America. Even after the Panama Canal was built, Nicaragua’s dream of constructing a larger, more advanced canal capable of accommodating ships with massive loads exceeding 300,000 tonnes remained unwavering.

However, numerous environmental and economic challenges impeded the realization of this ambition. The proposed canal site was plagued by fluctuating natural conditions, including frequent floods, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and the spread of tropical diseases. The land’s harsh geological characteristics further complicated any excavation plans, leading planners, at one point, to contemplate using atomic bombs to carve out sections of the canal route—an idea that would have caused severe environmental harm had it been executed.

Nicaragua has historically sought to offset its lack of experience and its limited scientific, financial, and technical resources by partnering with major powers such as the United States, Russia, and China. However, these efforts consistently met with immediate failure, as studies repeatedly revealed that the project’s costs far outweighed its anticipated benefits. The most recent attempt occurred in 2014, when a Chinese company began preliminary excavation at selected sites with plans to construct a canal featuring locks similar to those of the Panama Canal but with a significantly higher annual capacity. Nevertheless, the project was entirely abandoned by mid-2024 after the Chinese company failed to demonstrate its ability to complete it.

The ambition to build this canal is likely to remain a distant dream, with hopes now resting on the advancement of technologies that could one day make this complex endeavor feasible. The Nicaragua Canal project will also continue to be influenced by shifting domestic political interests, emerging and fading as needs dictate. However, a more practical alternative that Nicaragua may pursue in the near future involves expanding networks of railways, highways, and oil pipelines to facilitate the transport of goods that the Panama Canal can no longer handle due to the persistent drought affecting its lakes. Nicaragua’s projects are expected to compete less with the Suez Canal and more with the nearby Panama Canal, whose problems will likely worsen as global climate change persists.

5. Cape of Good Hope

This route was once the primary maritime corridor connecting the East and West from the late fifteenth century until the late nineteenth century. However, its significance began to wane with the opening of the Suez Canal in Egypt in 1869, which significantly shortened the distance between East Asia and Western Europe by approximately 26%—as illustrated in Table 1—and reduced travel times by an average of 20 days compared to the Cape of Good Hope route. Over the past decades, the Egyptian government has worked to expand and upgrade the Suez Canal, enabling it to accommodate global container ships of various sizes, along with 93% of the world’s bulk carriers and 61.2% of oil tankers.

Table 1: Comparison of distance savings via the Suez Canal and Cape of Good Hope routes

Source: Suez Canal Authority Statistics

The limited demand for international ships to use the Cape of Good Hope route has significantly contributed to the underutilization of African ports along this path, including those in Madagascar, South Africa, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, Senegal, and other West African coastal countries. This has, in turn, restricted the flow of development investments into these regions over the past decades, causing many of these ports, particularly container ports, to remain small or, at best, medium-sized. As a result, most of these smaller ports (see table 2) have been excluded from global competitiveness rankings. Even the few African ports that have managed to secure a position in these rankings have struggled, with their limited resources, to rise above the lower tiers.

Table 2: The 2022 global rankings of African container ports along the Cape of Good Hope route

Source: The 2022 Container Port Performance Index, World Bank

Note 1: This report assesses a mere 348 container ports worldwide.

Note 2: The ports of Guinea-Bissau and Gambia were not included in the report.

The security tensions that have flared up in the southern Red Sea since November 2023 have reignited interest in the Cape of Good Hope route. Many global shipping lines redirected their vessels to this alternative waterway instead of the Suez Canal, where insurance costs for passing ships skyrocketed twenty-fold between October 2023 and February 2024. International statistics show a booming Cape of Good Hope route, with ship traffic increasing by over 41% within a single year, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4: The volume of commercial ship traffic on the Cape of Good Hope route, July 2023–July 2024

Source: IMF-PortWatch

African ports are currently experiencing significant pressure and congestion, leading many passing ships to avoid docking there when possible. As a result, there is growing regional and international advocacy for the modernization of these ports to capitalize on the ongoing shifts in global shipping. However, investments in port development remain cautious, given the potential for traffic to revert to the Suez Canal, which could render investment in African ports ineffective. Additionally, there are concerns about the rise of piracy in West Africa, coupled with the limited capacity of West African countries to secure sea routes and the lack of effective coordination among them.

Over the next few years, efforts are expected to address the various challenges impeding the development of the Cape of Good Hope route. This will ensure it remains a viable alternative to the Suez Canal, which could face disruptions if similar crises occur. Advances in shipbuilding technology also promise to make the Cape of Good Hope route increasingly feasible, even if African ports along the route remain underdeveloped. Future vessels, equipped with clean, sustainable energy sources and larger cargo capacities, will navigate open waters, bypassing the draft limitations of the Suez Canal.

6. Ben Gurion Canal

In the early 1960s, the United States presented a groundbreaking proposal to Israel: to carve out a waterway that would link the Mediterranean and Red Seas, paralleling the Suez Canal. The proposed route would extend from Eilat on the Red Sea, traversing the challenging Negev desert and mountains, passing through Bi’r as-Sab’, and reaching the Mediterranean at Asqalan. The plan involved using hundreds of nuclear bombs to dig the 160-mile canal. Yet, the significant economic and political implications led to a rapid reconsideration, and the idea was eventually abandoned.

Figure 5: Map of the proposed waterway connecting the Red Sea and the Mediterranean

Source: Declassified report dated July 1, 1963, US Department of Energy archives

For decades, Israel has clung to the hope of constructing a canal parallel to the Suez Canal, attracted by the substantial economic and political benefits such a project could offer. To overcome the natural obstacles in the Negev and Aqaba deserts, Israel has proposed ambitious engineering solutions, including the construction of a canal with a lock system similar to the Panama Canal to address the challenge posed by the varying mountain heights in the region. However, studies have highlighted the immense difficulty of excavating through these rugged mountains, and the logistics of managing the vast amounts of water required for operating locks in the desert present additional complications.

Israel has revived its proposal, particularly in the wake of the Ever Given grounding, touting the Ben Gurion Canal as a seamless alternative, designed with two parallel lanes for outbound and inbound traffic. Tel Aviv promoted it as a solution to global shipping disruptions and has sought to persuade several affluent Arab countries, with whom it has recently reconciled, to join the project. However, this project remains largely aspirational, especially as attention shifts to the Indian Spice Route, which has captured the interest of both Israel and its regional and international partners.

In conclusion, while these six proposed waterways are not expected to challenge the Egyptian Suez Canal in the short to medium term, two of them—the Russian Northeast Passage and the Cape of Good Hope Route—could emerge as formidable competitors in the long run. This potential hinges on substantial investments in infrastructure and the development of commercial ships optimized for these routes.

References

Arabic References

Abdellah, M. (June 2024). Houthi Strikes on Maritime Navigation: Numerous Hits, Uneven Impact [hajmāt al-ḥawtẖy ʿala al-milāḥah al-baḥarīyah: ḍarabāt katẖīrah wa tā’tẖīrāt mutabāyinah], Egyptian Centre for Strategic Studies. Available at: https://t.ly/irOW4

Abdellah, M. (October 2019). The New Suez Canal: Five Years of Success [qanāt al-Suwais al-jadidah: khamasu sanwāt min al-najāḥ], Egyptian Centre for Strategic Studies. Available at: https://t.ly/ThYSS

Egypt State Information Service. (February 2022). The Suez Canal: The Lifeline of Global Trade [qanāt ạl-Suwais ạl-mamar al-melāḥie al-ạktẖar ahamiyah fī ḥarakat al-tijārah al-ʿālamīyah]. Available at: https://t.ly/e8qq9

Ibrahim, M. A. (January 2023). Bolstering the Suez Canal’s Competitiveness Against Alterantives Routes [ta’zīz tanāfusiyat qanāt ạl-Suwais fī mūwājahat ạl-ṭūruq ạl-munāfisah wa al-badīlah], National Security and Strategy Journal, Volume 1, Issue 1. Available at: https://t.ly/ec2an

Salama, N. A. (September 2023). The Ben Gurion Canal: Between Geography’s Rebuff and Colonial Ambitions [qanāt ben gūrīūin bayn rafḍ ạl-jugẖrāfīyah wa ilḥāḥ ạl-istiʿmār], International Association for Experts. Available at: https://t.ly/XgOsk

English References

Artic Portal. (2024). Northwest Passage, the Arctic Gateway Organization, Iceland. Available at: https://t.ly/kQiRv

Artic Portal. (2024). Northeast Passage, the Arctic Gateway Organization, Iceland. Available at: https://t.ly/7KhH-

Artic Portal. (September 20, 2023). Development in the Russian arctic, the Arctic Gateway Organization, Iceland. Available at: https://t.ly/B5RSj

Chen, J., Notteboom, T., Liu, X., Yu1, H., Nikitakos, N., and Yang, C. (2017). The Nicaragua Canal: Potential impact on international shipping and its attendant challenges, Maritime Economics & Logistics, Volume 21, pages 79–98. Available at: https://t.ly/HljW6

Emirates Policy Center. (April 2024). Disruption vs Expansion: African Ports and the Red Sea Crisis Challenges and Opportunities. Available at: https://t.ly/s15kQ

Maccabee, H. D. (July 1, 1963). Use of Nuclear Explosives for Excavation of Sea-Level Canal Across the Negev Desert. United States Office of Scientific and Technical Information. Available at: https://t.ly/cB_c2

Menarguez, A. B. B. and Flor, J. P. (2017). The new Panama Canal in Case Study of Innovative Projects – Successful Real Cases. IntechOpen. Available at: https://t.ly/T3qZI

US Army Center of Military History. (2009). The Panama Canal: An Army’s enterprise. US Army Center of Military History: Washington, D.C. Available at: https://t.ly/1SWVi