Netanyahu claims that the assault on Rafah is crucial for achieving victory. But is this really the case? Does this line of thinking hold water?

Israel’s moral defeat and the collapse of its security theory are widely acknowledged. Tel Aviv is now seeking an accomplishment that can be considered a victory in a war it was actually defeated. Israel has set a challenging objective in this conflict that started on 7 October, which is to eradicate Hamas. As part of the extensive sweep operations conducted by Israeli forces across the Gaza Strip, Israel affirms its intention to pursue Hamas members and demolish their infrastructure in Rafah.

As it strives to achieve this objective, the Israeli government disregards the international and regional opposition to its possible military operation in Rafah on the Egyptian border. Considerable consequences are imminent should Israel commence an expanded military campaign in Rafah. Israel’s potential operation may give rise to several legal violations, including breaching its obligations as the occupying state of an autonomous region and the 1979 agreements it signed with Egypt, let alone the humanitarian violations that are in contravention of both international humanitarian law and the international human rights system. Furthermore, the military operation planned by Tel Aviv may drive hundreds of thousands of displaced Palestinians to move towards Egyptian territory in Sinai, potentially breaching the border. There is also a chance that the Israeli army will initiate attacks on the Philadelphia axis, a scenario that Cairo opposes.

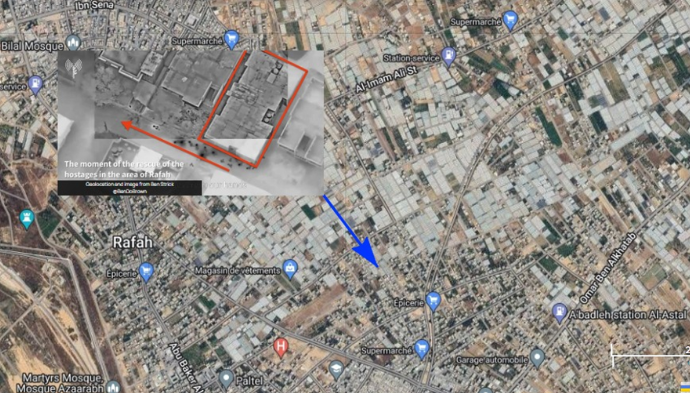

Israel’s Hostage Rescue Operation in Rafah

Israel conducted a raid on al-Shaboura camp in Khan Yunis, located over 7 kilometers inside Rafah, at dawn on 12 February, in order to rescue two hostages held by Hamas. The operation was executed by the Yamam Counter Terrorism Unit of the Israel National Police, with the support of auxiliary forces consisting of fighters from the elite naval commando unit Shayatet-13 and armored units from the 7th Armored Brigade. A C-30 aircraft specifically designated for intelligence eavesdropping operations provided technical assistance.

Fire support was conducted in two stages. The first was executed by Apache combat helicopters, which used missiles to hit targets on particular floors in the buildings next to the site where hostages were held. Israeli Special Force fighters were met with counterfire. Additionally, following the rescue operation, helicopters escorted the force out of the danger zone and later accompanied the hostage-carrying helicopter. As for the second phase of fire support, according to Israeli sources, it targeted a direct field command center in close proximity to the operation area in an attempt to limit Hamas’ response as much as possible, and then provide expanded strikes after the withdrawal of the Israeli force accompanying the hostages. The operation ended with the liberation of two hostages and the killing of 74 Palestinians, according to health officials in Gaza.

Despite the fact that only two out of 134 prisoners were freed from the Gaza Strip, Israeli media outlets portrayed the operation as one of the most significant prisoner liberation missions in Israeli army history.

The Israeli operation involved intricate tactics and coordination among different combat units. While military and political leaders used this victory to cover up the total failure Israel has been experiencing since Operation Al-Aqsa Flood, technical evaluations of the hostage release operation revealed that in addition to planning the entry and exit of the implementation elements, there had been a significant intelligence effort to locate the two hostages and special operations training to free them.

But the question remains: Was the operation’s true purpose solely to free two Israeli hostages, or showcase the destructive capabilities of an Israeli ground invasion in Rafah, or gauge the response of those opposed to an expanded Israeli military operation in Rafah?

Egypt’s Response to the Khan Yunis Operation

Egypt engaged in communication and coordination with different parties, including the United States, Israel, the Palestinians, and Qatar to achieve an instant ceasefire, de-escalation, and exchange of prisoners and detainees. Cairo also strongly advocated for heightened pressure on Israel to respond to these endeavors and abstain from taking any actions that might exacerbate the situation and detrimentally affect the interests of all parties involved.

Despite reiterating its dedication to upholding international law and honoring its agreements, Egypt approached the situation with a cautious and objective approach. This was achieved through the substantial fortification of its borders with Gaza, the creation of a 5-kilometer buffer zone, and the construction of concrete walls both above and below the ground. Additionally, it emphasized the need for collective international and regional endeavors to prevent the targeting of the Palestinian city of Rafah, which currently houses around 1.3 million displaced Palestinians, being the last safe area in the Gaza Strip.

In addition to these efforts, a round of negotiations was held in Cairo on February 13 with the participation of Israeli and American officials to discuss reaching a truce; however, the round ended without a specific proposal for the next phase.

Is Israel Going to Invade Rafah?

There are different opinions about how far Israel will go in its land invasion of Rafah and how successful efforts will be to broker a truce when it comes to the next phase of the Gaza conflict. According to various estimates, there are several possible scenarios, the most significant of which are listed below:

Scenario One: Israel will conduct a ground invasion of Rafah, as indicated by the Israeli Prime Minister’s firm determination for this course of action. Netanyahu’s political and possibly personal future is contingent on the continuation and possibly expansion of the state of war. He also aims to secure a decisive victory that will enable him to peacefully step down from power. Perhaps the encouraging response from the United States could serve as a source of motivation for him. Proponents of this scenario point to Netanyahu’s claims that there are multiple options for protecting civilians, in an attempt to appease the United States, similar to his earlier “claimed” willingness to establish safe passages for civilians to move to northern Gaza.

Scenario Two: Israel will respond to the ongoing negotiations and refrain from launching a land invasion of Rafah. This scenario suggests that the operation it conducted was to exert political pressure during the negotiations and enforce its own conditions, particularly after realizing that Hamas’s demands were inflated. Additionally, within the Israeli decision-making circle, a division exists between the military leadership and the far right-wing government. The Israeli military leadership asserts that the invasion of Rafah jeopardizes relations with Egypt and provokes the United States during the upcoming presidential elections. Additionally, Israel is experiencing significant economic challenges, resulting in immense pressure on the Israeli government. Moody’s downgraded Israel’s credit rating from A1 to A2 for the first time, attributing it to the economic impact of the Gaza war. The agency maintained a negative credit outlook, suggesting a potential further downgrade.

Advocates of this scenario further contend that the intricate and costly execution of the hostage rescue operation renders its replication arduous. When weighed against the time and energy needed to arrange the release of just two hostages, with the final tally standing at over 130, it is clear that the Israeli army will need months of planning to put a stop to this crisis, which is something that the Israeli public will not tolerate, even with the recent operation’s success. Indeed, the operation will function as a significant impetus for the surge in demonstrations that call for the release of the remaining captives.

Thus, proponents of this scenario conclude that Netanyahu and his government, despite their determination to persist in the war and eliminate the Palestinian cause, will likely have to turn to diplomacy for a prisoner exchange deal to safeguard lives during release operations. This negotiation process may involve various conditions and bargaining tactics that they excel at. This is a likely scenario, particularly if Hamas also sees negotiation as the best option to protect civilians.

Scenario Three: Supporters of this scenario argue that Israel’s course of action, whether to launch an invasion of Rafah and prolong the conflict or to engage in negotiations and depend on diplomacy, is contingent on various other factors. These factors include, above all, Israeli public opinion trends, the degree to which Israel is aware of the potential consequences of such a decision, and the extent to which the US administration has been able to contain Netanyahu’s intransigence by either securing his political status or working to remove him from the political scene and come to an agreement with another right-wing leadership that aligns with the prevailing trend in Israel. Additional factors include the effectiveness of pressure from Jordan, Egypt, and other countries in the region in persuading Israel to reconsider its impending decision regarding Rafah, as well as the accomplishment of all regional and international efforts to avoid impeding negotiations for a ceasefire and reaching an agreement on a prisoner exchange formula. On another level, an agreement between Hamas and the Palestinian Authority regarding who will lead the Gaza Strip’s governance—a technocratic government or some other arrangement—would make it more difficult for Israel to take advantage of Hamas’ continued presence in the Gaza Strip and prolong the conflict.

In conclusion, the next few days—and possibly even hours—will provide an answer to the question we raised here. Days will make it clear whether the release of Israel’s two hostages will provoke an invasion of Rafah in order to achieve the victory that Netanyahu desires, or whether it will serve as a catalyst for diplomacy and pacification that will compel real talks for a ceasefire—even if only temporarily. Some argue that Israel’s involvement in the negotiations will be only a waste of time until it gets ready for a major ground military operation in Rafah, while also preparing for its possible consequences and trying to appease the United States or to hedge against possible consequences.

Put succinctly, Israel has been defeated, and what it seeks will not change that. It is hoped that rational voices in Israel will be able to limit the losses and prevent the government from further expanding them.